It’s 1:00 am. It’s bitter cold outside, early December. Phil Trowbridge is making his first of three rounds throughout the night to check on his animals. He’ll do the same at 3:00 am, and then at 5:00 am, before even starting the day. It’s harsh, but it always has to be done, every day, even on Christmas.

He hears and sees one of the cows struggling. She’s panicked. When he gets close he knows his long work day is going to be even longer. Her entire reproductive system has prolapsed, and if he doesn’t act quickly, she’ll die.

Phil’s son PJ is with him helping, as he’s done all his life. They live just a stones throw away now that a neighbor sold his house to PJ. They run the farm together.

They get the cow into the chute and place her prolapsed uterus onto a makeshift table that Phil created on the fly, using a stretched feed bag. They raise a bar up under her to keep her from shifting, moving, and making an already dire situation even worse.

The climate in the Hudson Valley can be wet and icy. Her front legs slip forward while her back legs remain propped up from the bar. She tips forward. Now things could get really bad.

But it’s a happy accident. She can’t move, and her body is angled in such a way that it’s perfect for getting her insides back in place. Phil ties her front legs and pulls them forward, keeping her at that angle, while PJ – hands and arms numb with cold in the frigid, dark December air – puts their cow back together again.

RELATED: JOHNNY PRIME’S ONLINE BUTCHER SHOP

After spending a day with Phil and breaking bread with his family over dinner, I asked him and his son to tell me the most challenging and rewarding aspects of their profession. Phil told me that story, and it exemplifies both challenge and reward together in one grueling morning.

Phil has had to deal with maybe three prolapses in his decades of experience working with cattle, but he knows how to address the problem. In fact, he knows how to fix so much of what can go wrong on the farm, that if his veterinarians get a call, they’re truly worried.

I asked Phil and his son what the hardest part of their job is. Both he and PJ were modest: They told me it wasn’t a hard job, but I know I wouldn’t last a week doing what they do, day in and day out. Given the daily farm work on top of everything else they do, no one is ever idle.

While many things may come easy to Phil and PJ with their collective wealth of experience, there are still some things with which they have trouble.

Phil told me that losing an animal is hard. When that happens, it stays with him. His heart breaks. The roughly 400 animals in his care are like children to him. He checks on them all day, grows and mixes their food, feeds them, cleans them, monitors their health and keeps them healthy, delivers their babies… That’s respect. That’s love.

And from what I’ve seen it’s not just Phil; it’s all cattlemen who are worth a damn in this business. You don’t step into this lifestyle without respect and love for the animals. That’s something the average person doesn’t understand about our cattlemen.

Phil runs Trowbridge Farms – a patchwork of pastures, farms and barns that spans 1700 acres in Ghent, NY, about two hours North of Manhattan by train/car on the east side of the Hudson River.

Phil is originally from Buffalo, so this area may as well be Florida to him. When he first arrived here decades ago, he was surprised that cattle could even feed on pasture.

You may be thinking something like, “How the hell can someone run cattle in New York, where taxes and land costs are so high?” And that’s an excellent question.

The majority of land Phil works and uses is not his own. Rather, he rents and leases land from homeowners who are weekenders and summer vacationers from New York City. They own second homes, but allow Phil to raise feed crops and grasses there, and to graze his animals on the land, in exchange for rent or barter.

Because of this system, Phil can probably raise cattle cheaper than most places in the country. The relationships are mutually beneficial: Phil maintains the land, and the homeowners can sit back and earn additional income.

The soil here is everything. Across the Hudson, the earth is like clay, and therefore it’s harder to raise crops. Here, it’s more gravely and easier to work with. Phil couldn’t have this kind of productive operation if he didn’t understand the soil and how it affects plant makeup. In fact, there is pressure from dairy farms to get this better land for the alfalfa.

“Why?” For their feed.

Alfalfa is a high production, high nutrient legume plant that Phil uses in his cattle feed.

He takes three or four cuttings, and when I visited on July 2nd, he had already taken the first cutting. With his bromegrass and Timothy-grass farms, he only gets two cuttings. He also grows oats and corn as well, and makes his own hay and baleage.

Baleage, or silage, is a fermented feed that helps cattle in their digestion process. It also keeps longer without spoiling. That combination makes for an economically viable and nutritionally beneficial feed solution.

To make baleage Phil uses a vertical grinder and mixer first, to break up the feed crops. Then he covers it with tarp and weighs it down with specially cut tires that won’t collect water and draw mosquitoes. This allows the fermentation to occur and turn the crops into cattle feed.

While Phil grows and makes most of his own feed, he does buy some corn because it’s cheap. He also works with local distillers to get fermented corn mash byproduct, which is similar to baleage in its digestive benefits. It’s also a great way to reduce commercial waste and make good use of stuff that is otherwise discarded.

Cows love grain and alfalfa because they’re sweet. Alfalfa can be so rich, nutrient-wise, that at times Phil has to cut his feed with more fiber so that the cows don’t get too heavy.

“Why? Don’t we want big, heavy animals in the beef industry for price-per-weight values?”

It depends. In his sector of the business, Phil is primarily concerned with producing bulls and calves of good breeding stock and genetics, not to get them up to a high market weight for later eating, like what you often see at feed yards in the Midwest.

Phil ultimately wants comfortable females for breeding, and energetic, virile bulls for seeding. So, nutrient-wise, Phil takes different things into account because his end product is a much different animal, produced with a different purpose, than those produced in other sectors of the business: Phil’s animals are for breeding, while the others are for eating.

Speaking of Phil’s business, let me segue into more of what he does.

Trowbridge Farms is a seed stock operation, which means that Phil produces bulls that are eventually purchased by cow-calf farms. Since I know that you readers are at a remedial level when it comes to farm terminology, I’ll explain what this all means:

Bulls are intact males that can reproduce (steers are castrated, and can not reproduce). A cow-calf farm is a place where a permanent herd of cows gets pregnant and gives birth to calves, which are later sold.

Just prior to my visit, Phil had completed his annual bull sale. He averaged about $3,975 per head. That’s pretty fantastic, considering that his closest competition was bringing in half of that amount.

Phil hosts a yearly heifer sale (female cattle that have never been pregnant) and a calf sale as well. In addition he engages in many sales outside of his annual events.

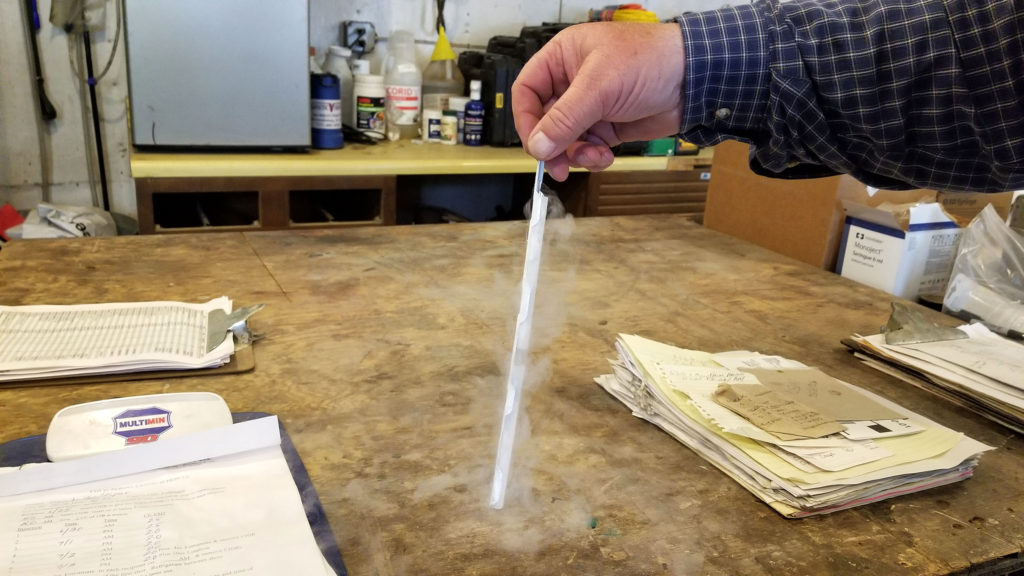

Phil also sells frozen bull semen and embryos with the use of vapor shippers. Cows can give birth about 10-12 times, on average, in their lifetime, before pregnancy becomes stressful on their body. But with embryonic science in play at Phil’s lab, he can get hundreds of fertilized eggs from his cows, freeze them, and use or sell them later. Given this aspect of the business, some of his cows have produced 500-600 offspring.

Almost all of Phil’s cows are surrogate mothers that were transplanted with embryos.

Timing is important when it comes to the cows. He schedules things around their super ovulation. First, CIDR (controlled internal drug release) devices are vaginally implanted – they’re like giant IUDs. This makes the cows think they’re ovulating, which allows him to synchronize all of their reproductive systems.

They get a follicle stimulation hormone, which produces lots of eggs. He then artificially inseminates them to fertilize the eggs with his bull semen, thereby creating embryos. The embryos are then flushed out and used or sold.

The process is just as intensive as human in vitro science. Phil’s daughter is an in vitro nurse and actually knows more than most doctors she works with, because she’s been doing this with cows for about 30 years.

In Phil’s operation, the bulls never touch a cow’s cervix. He usually puts embryos into cows fresh, as opposed to thawed from frozen, to increase the conception rate (15%-20% higher).

He sells a lot of frozen product to Argentina; about 40,000 units. But he makes more money from his US sales. This one bull, named Powder River, is like a legend around the farm. He’s spoiled and lazy, but he generates tons of product even at an old age – almost quadruple what other bulls can produce.

The frozen semen and embryos are stored in tubes or straws, and placed into liquid nitrogen holding tanks. In the event that Phil identifies a genetic abnormality, he will separate and retain the samples because many universities have expressed interest in studying them.

Phil’s customers are buying bulls, bull semen and embryos because they want specific genes to be expressed in their herds, and they know that Phil’s bulls produce some of the most desirable characteristics and embody superior genetics.

Customers look at these purchases as investments, like buying stocks. When they come to Phil, they usually don’t leave without buying.

Most of Phil’s animals are Angus. He has a few Hereford and cross breeds in the mix, but people know him for his superior quality Angus. Hereford cattle are notorious for suffering from pink eye in the summer months, so Phil has endeavored to breed his Hereford to have different eye traits so that his are less prone to pink eye.

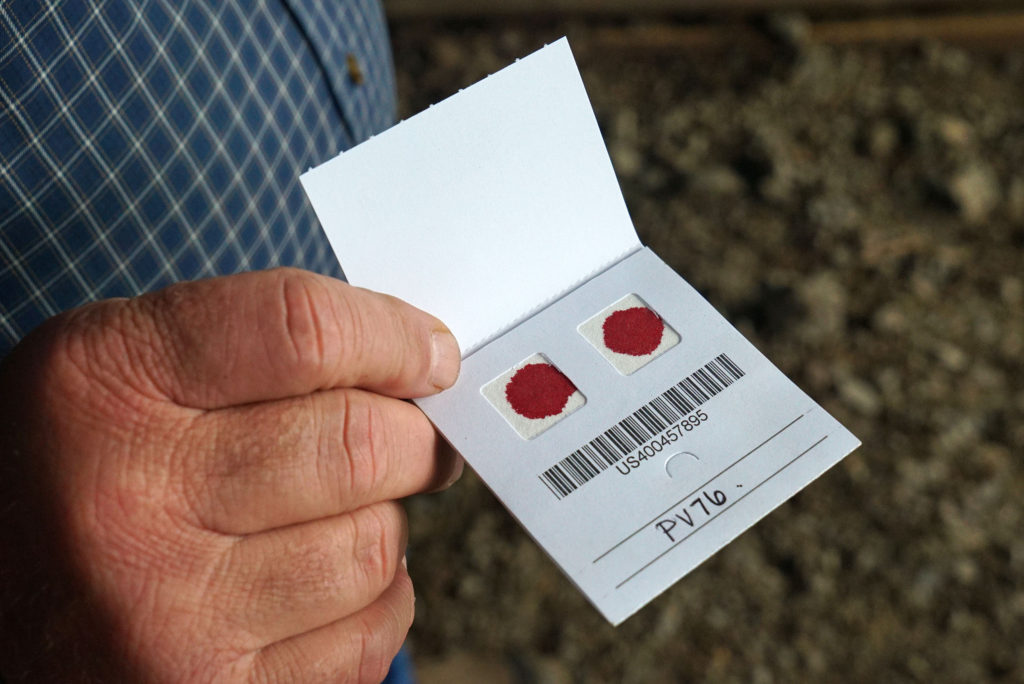

He has blood tests performed on every animal at a cost of about $50 a pop. Two drops of blood are taken and sent out to a lab.

These tests assess 50,000 different genomic markers that express traits related to things like parentage, marbling, tenderness, udder structure, temperament, body build and residual feed intake, among others. In addition to testing for these traits, the DNA samples are also used for parent verification.

“So what does the average day look like for Phil?”

Well, like most farms, Trowbridge is a family affair. Phil’s wife Annie does the books in the morning before heading to the hospital, where she’s a nurse on the surgical floor.

Phil’s son PJ is vital at the farm. He holds a degree in animal science from SUNY Cobleskill, and is the farm mechanic for all of the equipment.

Phil is usually up by 6:00 am, feeding and checking on the animals, and, thereafter, making hay in the Spring and Summer.

In Winter, he gets up an hour earlier to check on the cows. He recently installed video equipment in the barns so that he doesn’t always need to check on the cows several times overnight to see if they’re calving.

Calving is done twice a year: In early winter (January, February and March), and in the Fall. Calving in January means he can cut nine months of the process in working with bulls. Phil is focused on both human and animal safety, and bulls can fight each other and tear stuff up. He likes to sell them off before they turn two years old, because the older they get, the harder they are to manage.

Right now Phil is playing host to 4H kids for the Summer. They’re learning about cattle, hogs and lambs. The kids pick the animals themselves; they’re purchased on loan and then sold in September.

The kids learn how to take care of the animals, they keep track of feed and vaccinations with spreadsheets, and they show the animals at the county fair.

Many cattlemen work second jobs and perform odd tasks like this in their community. In addition to hosting 4H kids, Phil was the president of the NY Beef Council (which sponsored my tour here), he helped develop the new Veterinary Feed Directive laws that just went into effect, he runs a college internship program, and he goes on speaking tours for the industry. His son PJ has a tow truck gig at night, and he does some construction work for a friend in Albany when needed.

As if all of that isn’t enough, the Trowbridges also have to be vigilant of trespassing. A few months back, someone broke into the donor cow and calf barn behind the lab, took a bunch of video, and posted it online. Fortunately the guerrilla “coverage” was very positive in nature, but someone could have gotten hurt. And now sheriffs have been coming around, warning Phil that kids are stealing some of the ice packs used in shipping to make meth. Crazy.

Needless to say, no one is ever bored at Trowbridge Farms. But no one is resting on their laurels either. Phil wants to pass the farm on to his children, and beyond to his grandchildren.

He purchased his first barn there 25 years ago when it was a brush pile. He built it up and installed all the fencing little by little at night after spending his day working at a nearby farm. Since then his operation has become scientifically cutting edge and well respected in the community. Articles have been written in trade magazines attesting to Trowbridge’s advances in the field.

Not only is Phil’s farm economically productive and a benefit to both the industry and the community, but Phil is ecologically responsible and an excellent steward of the land.

Phil builds lasting relationships with everyone he encounters on a regular basis. I had the pleasure of hearing a message that someone left on Phil’s voicemail, thanking him for all he does in the area. The people of Ghent respect what he does, and he respects the people of Ghent. He even throws a hot dog and hamburger cookout for the locals each year that draws hundreds.

When Phil was driving me around the community, he pointed out some of the other business that came and went. Old chicken farms, welding shops, mechanic shops, well drillers, orchards, artist warehouse studios, craft breweries… And even some newcomers like grass finished, no antibiotics beef producers.

Some of these folks will allow their animals to die because they refuse to treat their cattle with antibiotics. Phil understands and respects the “no antibiotics” niche markets that have developed, but he’s also a big believer in medicine and cares for the animals too much to let one die when an illness is perfectly treatable.

His words: “If that doesn’t bother you, then there’s something not right.” In my opinion, this kind of attitude is absolutely necessary in order to work with animals to any measure of lasting success. Phil is by no means one of a kind within the beef industry when it comes to this outlook on animals, but that’s no slight to him. His work is demonstrative of how great the practitioners of this business are at its core. He’s exemplary, and exemplary is common in this business. That’s a good thing.

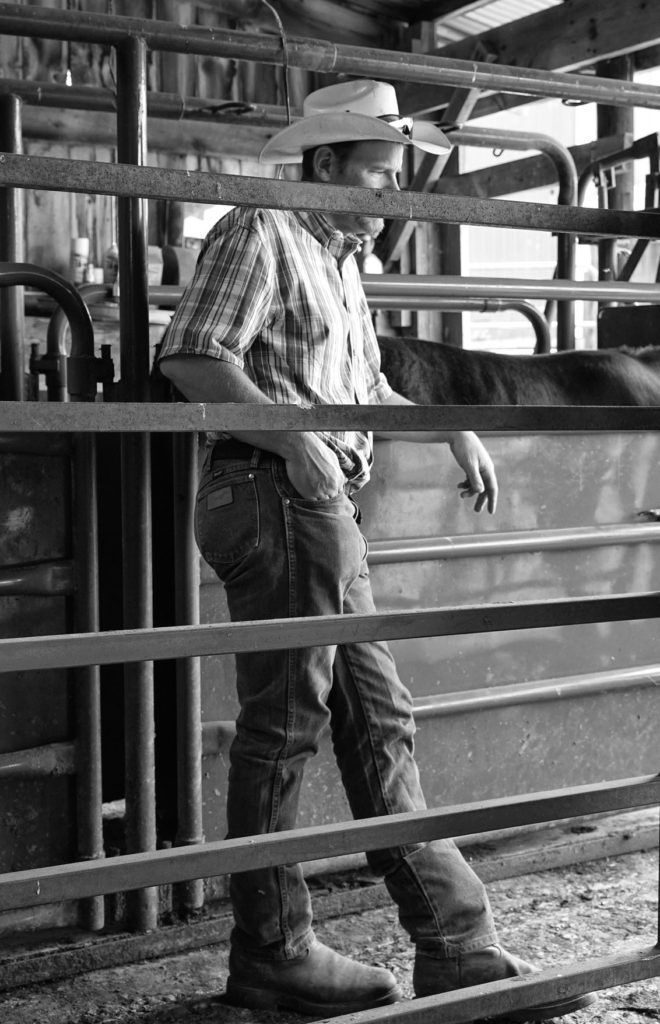

But Phil’s love for the animals he works with is instantly revealed to all the moment he encounters them. They’re calm in his presence, and very trusting of him and other people – even strangers like me. I’ve never seen anything quite like it.

The Trowbridge family name is celebrating 60 years in the cattle business this year. I’m very happy to have met Phil and his family, and I’m honored to put a spotlight on them for my readers.