CHECK OUT: MY BUTCHER SHOP

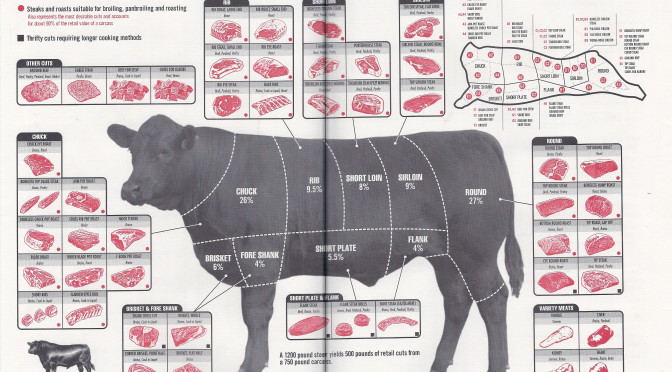

For those new to the world of steak, or for morons who are just not well-versed in steak lingo, this section should serve as a jumping-off point for all there is to know. The sections that follow trace the grades and quality, the origins, anatomy and cuts, the cooking styles, and the flavors of meat. Stop drooling and read on… ONWARD TO THE STEAK!

There are several common cuts of steak on a typical steakhouse menu. If a steakhouse doesn’t have some of the main choices, then it needs new management, or perhaps it is not a real steakhouse. These essential cuts are described and pictured below:

The Ribeye:

In most circles this is the true steak eaters steak; this is the real flavor of meat. A man’s steak, possibly only rivaled by the porterhouse in testosteronic manliness. As a connoisseur of meat eatery I will almost always go to the rib chop to really test the mettle of a steakhouse to its very bones. It is cut from the rib of the animal, and has a circular shaped chunk of meat encased in a thin layer of gristle just off the bone. In the center of the circle of carnivorous delight, there is ideally some good quality, melt-away marbled fat dispersed throughout. Don’t be alarmed at this. Good preparation of quality ribeye steaks will render the fat into a liquid – meaning the fat melt into the meat and add flavor to it. My favorite part of the cut, however, is the outer ridge, outside the gristle and away from the bone. This section is often several times more tender and juicy than the center of the chop, and it absorbs flavor like a sponge, so savor every bite. Some restaurants will call the ribeye a “tomahawk steak” if the entire rib bone is left on and french cut by the butcher, since it then looks like a small hatchet. It is common for butchers to cut the bone down a bit, however, for packaging purposes. In its unbutchered form, it is a tear-drop shaped slab of beef containing several steaks along each rib. French cutting exposes the bone neatly, trims away the excess and portions the ribs out into individual steaks. The ideal way to eat a good ribeye is simply grilled or broiled with kosher salt and cracked black pepper. A favorite for home cooking is to treat it beforehand with some olive oil and garlic if the quality is not prime (standard grocery store cuts), and then cook on a high-heat gas grill or BBQ for a few minutes on each side. Sizes and portions range from anywhere between 14oz to 36oz, most often hovering around the 20oz mark in restaurants. Often times it is seen served boneless, bone-in but with a shortened bone, or roasted whole and sliced as “prime rib” with some juices.

The Filet Mignon:

The Filet Mignon, meaning cute or dainty filet, is essentially a tube of “tenderloin” meat that runs along the spine of a steer. There isn’t much of it per animal, so it is coveted by meat enthusiasts, and therefore often expensive. It is possibly the most lean, tender part of the animal, so it makes for a great steak. This is the meat of aristocrats. Carnivore connoisseurs will argue tirelessly over which is the most flavorful cut – the ribeye or the filet. My personal opinion is that the ribeye offers the most flavor, but the filet consistently offers the best quality cut of beef. Cooking a filet at home can present a challenge in avoiding uneven distribution of color, since, to get a large enough portion size, the meat often has to be cut thick. The outside can be overdone and the inside underdone. Masterful meat mongers and manipulators know how to get the job done, however, so have no fear. Sizes range from 6-8oz petit filets (sometimes served alongside lobster for a “surf & turf” meal) to 10oz-12oz standard filets. The term filet actually means boneless, but there is a trend lately to leave a portion of a nearby bone attached to the filet to impart a more rich flavor to the meat. Hence the self-defeating, paradoxical “Bone-in Filet” verbiage you may see on a menu. Common modes of preparation are roasted with a sauce (sometimes whole, banquet style after the tough “silver skin” is removed, as done with chateau briand), grilled, or broiled. More recently masterful chefs have surmounted the problem of uneven cooking and temperature distribution by using the sous vide cooking method. Raw preparations include tartar (finely chopped) and carpaccio (thinly sliced and pounded/tenderized), usually served chilled and drizzled with olive oil, sprinkled with fresh herbs and garnished with micro greens and shaved hard cheese (such as parmigiano). The raw preparations are my favorite, and often times show up as an appetizer on steakhouse menus. Nothing better than getting ready to eat a grilled steak by… eating some raw steak!

The Strip Steak:

The strip steak is most often called the NY Strip, and often times called the Kansas City strip. But screw that city. New York is king. It may also be seen as a “shell steak” but that term is often associated with lower quality cuts The strip is cut from the short loin, from a muscle that does little work, like the filet. It contains fat in levels that are somewhat in between the tenderloin (virtually none) and the ribeye (plenty of good, melty fat), and has flavors and textures that are more uniform throughout, unlike the ribeye which has varying textures. For me, the Strip is best at medium or medium rare, to preserve the tenderness, and at a really great quality, something prime+. Generally I will try the strip at a steakhouse only after I have tried the ribeye. You will often see it marinated or rubbed with spices, to impart additional flavors, but grilling and broiling in the traditional style is fantastic as well. It can be served bone in or boneless. Leaving the bone in will impart more flavor and help with the cooking process, since the bone conveys heat into the center of the meat while locking in juices. At home, marinade this puppy in something like soy sauce and garlic, and slap it on the BBQ for a few minutes on each side and you will have the perfect home-cooked steak.

The Porterhouse:

Quite simply, the porterhouse is two steaks in one, a strip on one side, and a filet on the other, separated by a bone – the vertibrae. This is why you will often see it served “for two” – meaning two people – because they can be quite large (anywhere from 24oz to 48oz for a single portion, to more for multiple people). But screw that – eat it all yourself and be a man. Sharing is for assholes and pussies anyway. The porterhouse for two is often served on a steaming hot plate right out of the broiler, pre-sliced while it is still on the rare side, and then allowed to cook the rest of the way on the hot plate as you shove slice after delicious slice into your mouth and down your esophagus after dipping your meat in its own juices and masticating.

Want more info on those four cuts of beef? Check out Meat 201.

Below are some other cuts less commonly seen on steakhouse menus, though some are becoming more popular lately. If a steakhouse doesn’t have all these items, they don’t need to close up shop. However, I feel that every chop house should have at least the four main cuts above and perhaps Something from below: one or two preparations maybe, just to have some other options.

The T-bone:

After a certain stretch of vertibrae, the size of the tenderloin part of the Porterhouse gets smaller, and the strip side gets a little tougher, so the cuts are no longer considered top quality porterhouse, but, instead, standard T-bone steaks. They are often cut thin and flash fried or grilled. You don’t see them on steakhouse menus often, since they are not top quality, but they still have a lot of flavor and can be creatively prepared.

The Flank:

The flank is cut from the abdominal muscles. It is broad, long and flat with heavy striations or grain in the meat. As such it is much tougher than the other beef cuts, and therefore moist cooking methods such as braising are often used. It can also be quickly seared in a hot pan and eaten on the rare side to maintain tenderness. Flank steak is best when it has a bright red color. Because it comes from a well-exercised part of the animal, it is best prepared and eaten when cut across the bias or grain in the meat. Most stir-fried beef dishes and fajitas are prepared with this cut of beef (cut into small pieces and tenderized heavily). Other preparations include marinating or service with a chimichurri sauce.

The Skirt:

Skirt steak is not vagina. It is a long, flat, striated cut loved for its bold flavor. The outside skirt steak is the trimmed, boneless portion of the diaphragm muscle. This is covered in a tough membrane that should be removed before cooking. The inside skirt steak is a boneless portion of the flank trimmed free of fat and membranes. Skirt steak is also used for making fajitas, stir-fry dishes, and Bolognese Sauce. To minimize their toughness, skirt steaks are either grilled or pan-seared very quickly with high heat or cooked very slowly on low heat, typically braised, like the Flank. Similarly, because of their strong graining, skirt steak is sliced across the grain for maximum tenderness. To aid in tenderness and flavor, they are also often marinated. The skirt steak is sometimes called Roumanian steak. It is commonly grilled or barbecued whole, sometimes served with a chimichurri sauce.

Located near the flank and the skirt is also the Bavette cut.

The Hanger:

Sometimes known as “butcher’s steak” because butchers would often keep it for themselves rather than offer it for sale, the hanger is derived from the diaphragm. Hanger steak resembles flank steak in texture and flavor. It is a vaguely V-shaped pair of muscles with a long, inedible membrane down the middle. The hanger steak is best marinated and cooked quickly over high heat (grilled or broiled) and served rare or medium-rare, to avoid toughness. Anatomically, the hanger steak is said to “hang” from the diaphragm of the steer. The diaphragm is one muscle, commonly cut into two separate cuts of meat: the “hanger steak” traditionally considered more flavorful, and the outer skirt steak composed of tougher muscle within the diaphragm. Occasionally seen on menus as a “bistro steak”, hanger steak is generally marinated, grilled and served with chimichurri sauce. it can also be used for tacos or fajitas with a squeeze of lime juice, guacamole, and salsa.

The Shank:

The shank is the upper leg. Due to the constant use of this muscle by the animal it tends to be tough, so is best when cooked for a long time in moist heat, such as a braise. As it is very lean, it is widely used to prepare very low-fat ground beef. Beef shank is a common ingredient in soups and stock.

The Sirloin:

Sirloin is a steak cut from the rear back portion of the animal, continuing off the short loin from which T-bone, porterhouse, and club steaks are cut. The sirloin is actually divided into several types of steak. The top sirloin is the most prized of these. The bottom sirloin is less tender, much larger, and is typically what is offered when one just buys sirloin steaks instead of steaks specifically marked top sirloin. When the fat cap is left on this cut, it is called picanha in many south american countries.

The Flatiron:

Flatiron steak is from the shoulder and is usually 8oz to 12oz. They usually have a significant amount of marbling and can be very tender. It has become popular at upscale restaurants to serve flatirons from Wagyu beef, as a way for chefs to offer more affordable and profitable dishes featuring Wagyu or Kobe beef. It is also commonly referred to as a top blade steak, or an oyster blade steak (sometimes cut across the grain instead of along the seam of connective tissue that runs through the middle).

Directly beneath this cut is where you will find your Teres Major, or shoulder tender steak. You can also find the Denver Cut within the chuck shoulder as well.

Beef Short Ribs:

Beef short ribs are chunks of meat from along the ribs that are highly marbled with fat. Improper cooking can lead to tough texture. Often you will see “braised beef rib” on a menu. This is basically cooked in liquid, slow and low, until the thicker fat melts away, leaving you with extremely tender and soft, flavor infused meat. Some grocery stores, and asian markets in particular, have short ribs that are cut thin (a quarter to a half inch thick), sometimes with two or three cross sections of rib bones embedded within. The best way to prepare these thin cuts is to soak them in a marinade and then grill on high heat for a minute or two on each side.

Spare Ribs:

Spare ribs are the most inexpensive cut ribs. They are a long cut from the lower portion of the animal, specifically the belly and breastbone, behind the shoulder. There is a covering of meat on top of the bones as well as between them.

Brisket:

Brisket is a cut of meat from the breast or lower chest. These muscles support about 60% of the body weight of standing/moving cattle. This requires a significant amount of connective tissue, so the resulting meat must be cooked correctly to tenderize the connective tissue. Slow and moist cooking methods are most common, utilizing spice rubs or marinades, then cooking slowly over indirect heat from charcoal or wood. This is a form of smoking the meat. Additional basting of the meat is often done during the cooking process. This normally tough cut of meat becomes extremely tender brisket, despite the fact that the cut is usually cooked well beyond what would normally be considered “well done”. The fat cap often left attached to the brisket helps to keep the meat from over-drying during the prolonged cooking necessary to break down the connective tissue in the meat. Water is necessary for the process. The finished meat is a variety of barbecue. Other methods of preparation usually include braising or boiling for long periods of time, such as pot roast or corned beef, and sometimes spicing for making pastrami.

Chuck:

The typical chuck steak is a rectangular cut, about 1″ thick and containing parts of the shoulder bones. This cut is usually grilled, broiled or cooked with liquid as a pot roast. The bone-in chuck steak or roast is one of the more economical cuts of beef. It is particularly popular for use as ground beef, due to its richness of flavor and balance of meat and fat. The average meat market cuts thick and thin chuck steaks from the neck and shoulder, but some markets also cut it from the center of the cross-rib portion. Short ribs are cut from the lip of the roll. The chuck contains a lot of connective tissue which partially melts during cooking. Meat from the chuck is usually used for stewing, slow cooking, braising, or pot roasting.

The Chopped Steak:

Essentially a large hamburger; it is chopped meat or ground beef.